Willa Cather and The New York Times Book Review

Margaret Anne O’Connor’s Introduction to Willa Cather: The Contemporary Reviews argues that the collection of published responses to Cather’s work “no doubt says as much about the health and vitality of the reviewing community as it does about the specific literary works reviewed.”1 O’Connor makes various generalizations about Cather’s reviews as a whole: that responses to her work varied greatly; that debates over Cather’s merit seemed to function as proxies for larger points of disagreement; that no single book of Cather’s was regarded as her epitomizing work.3

My presentation asks what it might mean to think about Cather’s contemporary reviews in a context closer to how they were originally read: as an occasional entry in a larger, ongoing series of book reviews about many other books and authors. For the purposes of this talk, I’m focusing on The New York Times as a collection of such reviews. I will concede that most readers of reviews probably browsed book review sections for interesting looking entries rather than reading every review, and that most readers of periodicals were probably consulting more than one reviewer’s opinion before dedicating time to a book and/or spending money on it, but I think The New York Times is a useful lens for my approach for two reasons:

First, The New York Times has become the nation’s paper of record; as a result, it is digitally accessible, with a well-designed search engine and relatively high quality data “under the hood.” Although it is far from perfect, I was able to work with The New York Times to license this underlying data and run relatively sophisticated analysis of thousands of reviews collectively. From a biographical perspective, it wasn’t the most important periodical in Cather’s life and work but, in Cather’s lifetime, The New York Times Book Review grew substantially.

It began in 1896 as a Saturday section of only eight pages and was, according to Richard Kluger, little more than “a collection of book reports to consumers on the readability of new titles.”3 It became a Sunday supplement in 1911, spent two years between 1920 and 1922 as The New York Times Book Review and Magazine, and grew after 1922 into a highly respected book review insert of the Sunday edition of The New York Times, as many as 96 pages in length at its height.4

Second, The New York Times Book Review exemplifies an important, contested trend in book reviews, which is best described by Joan Shelley Rubin in The Making of Middlebrow Culture as the “news approach” to book reviews.5 Such reviews emphasized book summaries, and gave general recommendations to consumers. According to Rubin , the genteel editors of the previous era were more philosophical: “Imbuing their editorial stance with their belief in discipline, autonomy, and morality as components of culture, they conceived of themselves as carrying out their mandate to educate public taste.”6 The New York Times Book Review was founded on this principle; in the words of book review editor E. Francis Brown, “It may be that the deliberate aim to treat ‘book as news’ came later on, but it was at least the ‘news feature’ that dominated the columns of the first Book Review.”7 Focusing on The New York Times is meant to connect Cather to this topic.

The overarching idea of this presentation is to think about the agency of The New York Times Book Review, as a publication with employees who had their own goals, which grew and changed over time. Here Cather was one writer among many, whose status also changed over time. Examining reviews of Cather’s work in their original bibliographical context demonstrates this point. By focusing on The New York Times Book Review, we can also better appreciate some of trends that framed Cather’s work in this particular publication, as well as a complex network of associations linking Cather to other authors and categories.

Foremost, returning to The New York Times Book Review and reading widely reminds us that Cather was one author among many, especially at first. The Book Review, like many periodicals, elevated books and authors as they gained status. Beginning with April Twilights in June of 1903, The New York Times Book Review published reviews of Cather’s books on at least 20 occasions; many of these write-ups were lengthy and prominently displayed, but Cather was first mentioned as an unknown but positively regarded newcomer. The first review mentioning her, for example, was dedicated to three books of poetry: Summer Songs in Idlenesse by Katharine H. McDonald Jackson, Sonnets and Lyrics, by Katrina Trask, and April Twilights. Jackson’s poems had “the charm of sincerity”; Trask’s merits were “chiefly confined to the thought”; she was “not entirely fortunate when it comes to the musical flow of words and the purity of vowel sounds. To make ‘ambassador’ rhyme with ‘wings astir’, for example, is rather more than audacious.”8 This framing is omitted from the excerpted version in Willa Cather: The Contemporary Reviews, which is completely reasonable for a book that seeks to collect reviews of work by Cather, but also distortive in terms of Cather’s position in that book review.

When we turn to The New York Times’ TimesMachine for digitized versions of Cather’s reviews, we gain a much stronger sense of Cather’s changing position, and especially her rise to prominence. Popular and acclaimed authors; books on subjects of wide interest; and books that had caused a stir, in general, were given more prominent placement in The New York Times Book Review (and other periodicals). My sense of “prominent placement” includes:

Some of these changed over time; for example, author photographs were an increasingly common accompaniment, in the nineteen-teens, for authors highlighted by The New York Times Book Review, and they had become a staple of the supplement by the 1920s.9 There were most certainly additional markers of prominence, both bibliographical and rhetorical, but I would argue that the six I’ve described were especially important in the context of The New York Times Book Review.

Here we see the review The Song of the Lark, framed in relation to the lead review of Selma Lagerlöf, “the woman who won the Nobel Prize” in 1909. Lagerlöf is in the banner headline, on the front page, with artwork. Dear Enemy by Jean Webster is at the bottom of the front page, in a position of secondary prominence. The Song of the Lark is the sixth review, after two page jumps.

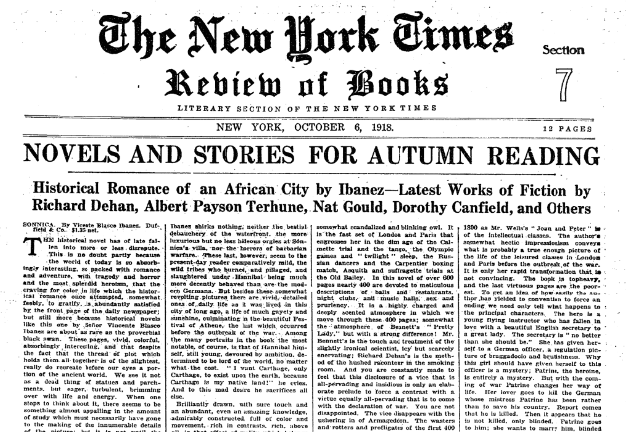

Here is a similar example, in which the review headline establishes Ibanez as a lead review, mentions “Richard Dehan, Albert Payson Terhune, Nat Gould, Dorothy Canfield, and Others.” Cather’s My Ántonia was one of these others, again after two page jumps. Dorothy Canfield’s 1922 review of One of Ours had a named author and was the lead review in “Latest Works of Fiction,” but it appeared on page 14 of the Book Review; A Lost Lady was also the lead review in “Latest Works of Fiction,” as was The Professor’s House. Louis Kronenberger’s review of My Mortal Enemy was Cather’s first single work to include an image of the author, though it was a harsh review, and Cather told Blanche Knopf in a letter that she hadn’t seen the notice, and would “avoid seeing it—just as well, as it’s by someone whose opinion one needn’t regard.”10 Kronenberger had previously reviewed The Story of Novel, and Other Stories, by Maxim Gorky; and Edna Ferber’s Show Boat, and he went on to write numerous reviews for The New York Times Book Review.11

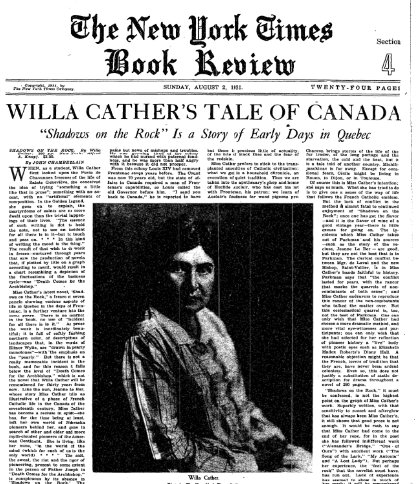

Cather’s first appearance on the front page of the Book Review was in August 2, 1931, when John Chamberlain reviewed Shadows on the Rock. Chamberlain, in one obituary, was described as “one of America’s most trusted book reviewers.”12 His review of Shadows on the Rock included artwork of Cather, a photographic portrait by the New York Times Studio. For all this, Chamberlain describes Cather’s work as “plotless” and writes that “the lack of conflict in the method is almost fatal”—in short, “not the highest point on the graph of Miss Cather’s work.”13 Yet this was arguably the high point of her bibliographical presentation in The New York Times Book Review to date, and reviews of her work remained prominently placed thereafter, including front page coverage for Obscure Destinies and Lucy Gayheart, as well as artwork and prominent placement for Not Under Forty, Sapphira and the Slave Girl, and The Old Beauty and Others.

Cather, like so many others, essentially began her career as a face in the crowd and earned credibility with The New York Times Book Review over time. Her stature as an author should not be conflated with positive reception; in fact, as others have pointed out, reviews became increasingly negative as her prominence grew. Rather, we should think of review individuation and review sentiment as two related but separable axes of assessment. I believe it fair to say that bibliographical markers of individuation were the result of editorial judgment, which were influenced by the specifics of each case [what is news?], and by larger patterns of coverage evident when The New York Times Book Review is regarded at a larger scale.

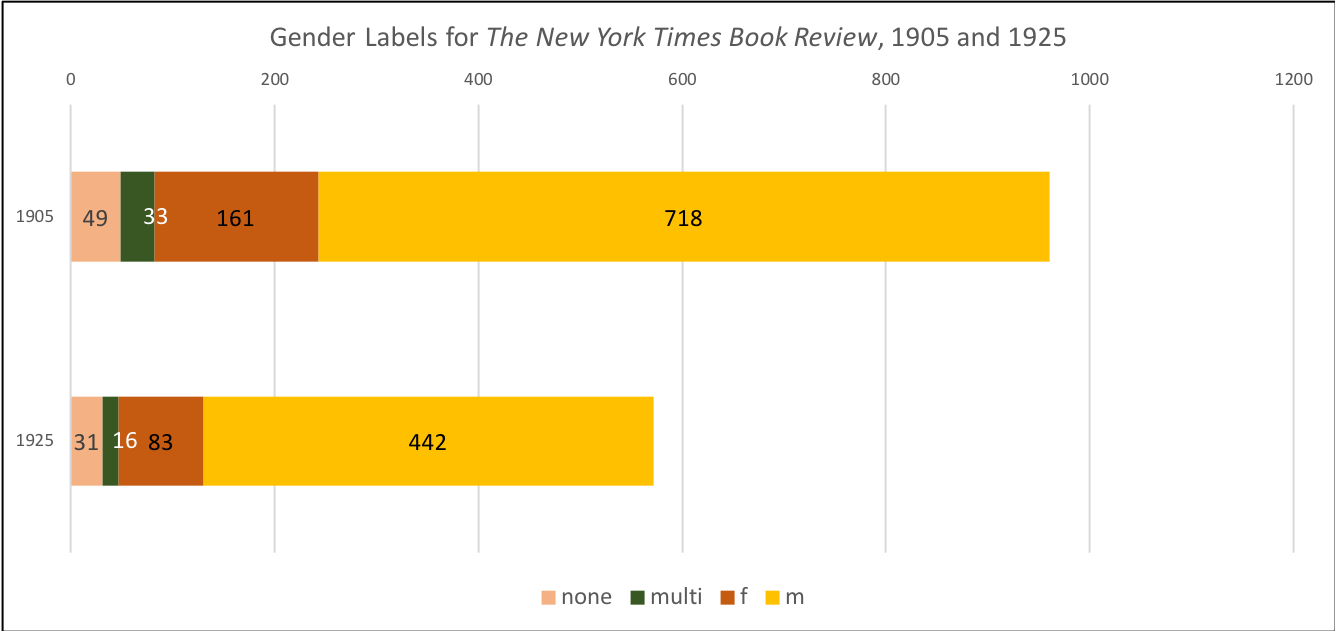

I hope that I will surprise no one here when I say that review individuation came much more easily for male authors. This generalization is much more apparent when The New York Times Book Review is the object of study, rather than one author’s reviews. My most recent scholarship on gender norms in The New York Times Book Review has involved sampling reviews published in that venue between 1905 and 1925, and tagging them as reviews of “assumed men,” “assumed women,” “multi-gender,” and “gender unknown or unstated.” Rather than view gender as an essential category, I attempt to trace the history of reviewers’ perceptions and the gender norms they reveal. In the process, I have made more comprehensive inventories of reviews for 1905 and 1925, and I have found approximately a six-to-one gender disparity in single work reviews.

However, this disparity is at least in part an effect of a tendency to group women together in larger reviews of multiple works. Review titles like “The Poems of Two Women”; “Women as Novelists”; and “Women Who Write Popular Books” appeared regularly.14 Reviews on the front page were more than ten times more likely to be authored by men than women.15 There have been 19 editors of The New York Times Book Review since its inception in 1896; 17 were men, and two have been women, counting the current editor Pamela Paul among this number; (its first female editor was named to the role in 1989.) Named reviewers between 1905 and 1925 were mostly men. Some may assume that only women would review women, but this was not the case.

In fact, out of 129 signed reviews of work by women in the inventory I conducted, 97 were written by men and 32 by women. However, those 32 reviews were written by only 22 different female reviewers. Gender disparity among book reviewers and in book reviews continues to this day. A recent analysis of The New York Times Book Review found the contemporary gender imbalance of reviews to be 2:1 in favor of male-authored work; an Australian study found a recurring ratio between 3:2 and 7:3 of gender disparity over the past thirty years despite a considerable increase in the proportion of books by women.16 I would hypothesize that the norms I’m describing were typical for many if not most newspapers and magazines of the early twentieth century.In this context, men more readily stood out as individually newsworthy.

Previous biographical criticism has established Cather’s ambivalence about being lumped in with other female authors, as well her willingness to criticize women’s writing. She could not, however, will herself free of the associational network that linked her to these trends. For example, in a review titled “Militant Feminists,” reviewer Rose C. Feld criticized Amy Wellington’s Women Have Told (1930) for omitting Willa Cather and Edith Wharton from the category of feminist authors.17 This kind of association, introducing the idea of Cather as both non-feminist and feminist, helped establish boundaries for a debate about Cather’s identity and allegiances. Similarly, a 1926 book review of Martha Ostenso’s The Dark Dawn, with the headline “A Domineering Woman”, mentions Cather by way of contrast: “Miss Ostenso might do well to study Willa Cather and observe her narrative technique and treatment, for it isn’t necessary to resort to melodrama to write persuasively of simple people.”18 Here the reviewer compares a new book to a standard set by Cather but also frames her as an opponent of melodrama.

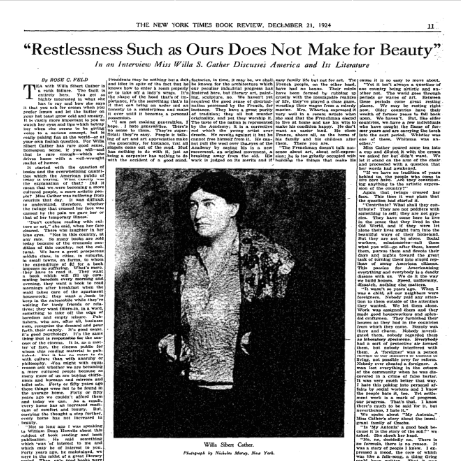

Reading Cather’s reviews in the print context of The New York Times Book Review produces a dizzying number of potential associations. A major interview of Cather appeared in the Book Review in 1924—in a January 1925 letter, she complained about having her words distorted into a critique of Americanization, and a general rebuke of social workers.19 (The interviewer, Rose C. Feld, went on to write “Militant Feminists,” among other things.) In 1923, Herbert S. Gorman’s feature, “Willa Cather, Novelist of the Middle Western Farm” appeared in the Book Review. Cather was also mentioned in various non-review content, such as when she made the news for winning a prize, when other prominent authors (like Sinclair Lewis and E. A. Robinson) praised her work, when movies based on her work were reported on or reviewed, or when rare or fine editions of her work sold at auction. She appeared regularly in paid advertisements for her books; especially after leaving Houghton Mifflin for Knopf, and previews of her work were often included in recurring columns like “Books and Authors” and “Books To Come Before Christmas.”

I began this presentation with the hope of highlighting the agency of The New York Times Book Review, with that idea that reframing my focus would reveal a slightly different version of Cather, as one author among many, as one icon defined, redefined, and disputed across a vast network of descriptions, comparisons, and associations. I believe this reframing draws a sharper picture of Cather in relation to individuality, gender, and genre. But the next step for this work is, I would argue, especially daunting because it involves not merely describing Cather as one among many, but describing potentially hundreds periodicals and thousands of authors as many among many. What would it mean to account for how cultural hierarchies were mediated by periodicals? I’ll get back to you on that.

Endnotes

- getting a front page book review

- having a single work review rather than being part of a feature that reviewed multiple works

- being the lead review in a recurring feature like “Latest Works of Fiction”

- having more than one review of a single work

- attaining a review by a named review author

- having artwork appear with a review.

- O’Connor, Margaret Anne, ed. Willa Cather: The Contemporary Reviews (Cambridge University Press, 2001), xxiv.

- O’Connor, xviii.

- Richard Kluger, qtd. in Joan Shelley Rubin, The Making of Middlebrow Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 92.

- Brown, E. Francis. The Story of The New York Times Book Review (The New York Times Company, 1968): 7, 9, 18.

- Joan Shelley Rubin, The Making of Middlebrow Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 1992), 35.

- Rubin, 37.

- Brown, 10.

- “Recent Poetry. Various Publications of Mr. Richard Badger of Boston,” review of Summer Songs in Idlenesse [by Katharine H. McDonald Jackson], Sonnets and Lyrics [by Katrina Trask], and April Twilights [by Willa Sibert Cather]. The New York Times Saturday Review of Books and Art. June 20, 1903: 434. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1903/06/20/102009155.html?pageNumber=20

- Similarly, norms for single work reviews changed over time. The Troll Garden and O Pioneers! were both reviewed before “Latest Works of Fiction” became more common.

- Willa Cather to Blanche Knopf, October 24, 1926. The Selected Letters of Willa Cather, eds. Janis P. Stout and Andrew Jewell (Knopf, 2013), 387-388.

- Kronenberger, Louis. “Five New Tales in Modern Manner by Maxim Gorky,” review of The Story of a Novel, and Other Stories [by Maxim Gorky]. The New York Times Book Review. June 14, 1925: 9. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1925/06/14/119049554.html; Kronenberger, Louis. “‘Show Boat’ Is High Romance,” review of Show Boat [by Edna Ferber]. The New York Times Book Review. August 22, 1926: 5. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1926/08/22/104212714.html?pageNumber=39

- Opitz, Edmund A., “A Reviewer Remembered: John Chamberlain 1903-1995,” The Freeman 45.6 (June 1,1995). https://fee.org/articles/a-reviewer-remembered-john-chamberlain-1903-1995/

- Chamberlain, John. “Willa Cather’s Tale of Canada: ‘Shadows on the Rock’ Is a Story of Early Days in Quebec,” review of Shadows on the Rock [by Willa Cather]. The New York Times Book Review. August 2, 1931: 1. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1931/08/02/92152424.html?pageNumber=27

- Rittenhouse, Jessie B. “The Poems of Two Women” January 29, 1911: 38. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1911/01/29/104818909.html?pageNumber=18; “Women as Novelists,” The New York Times Saturday Review of Books. May 2, 1908: 254. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1908/05/02/104802959.html?pageNumber=22Notman, Otis. “Women Who Write Popular Books,” The New York Times Saturday Review of Books. February 23, 1907: 110. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1907/02/23/106741545.html?pageNumber=20

- Single focus reviews on the front page of the Book Review numbered 151 in my sample, 136 by men and 15 by women.

- Hu, Jan C. “The Overwhelming Bias in New York Times Book Reviews,” Pacific Standard Magazine Online. August 29, 2017. https://psmag.com/social-justice/gender-bias-in-book-reviews; Harvey, Melinda, and Julieanne Lamond, “Taking the Measure of Gender Disparity in Australian Book Reviewing as a Field, 1985 and 2013,” Australian Humanities Review 60 (November 2016): 84-107.

- Feld, Rose C. “Militant Feminists,” review of Women Have Told [by Amy Wellington]. The New York Times Book Review. March 23, 1930: 26. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1930/03/23/113331179.html?pageNumber=46

- “A Domineering Woman,” review of The Dark Dawn [by Martha Ostenso]. The New York Times Book Review. October 24, 1926: 6. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1926/10/24/98400254.html?pageNumber=35

- Feld, Rose C. “Restlessness Such as Ours Does Not Make for Beauty,” The New York Times Book Review. December 21, 1924: 11. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1924/12/21/101629351.html?pageNumber=43; Willa Cather to Miss Teller, January 21, 1925. The Selected Letters of Willa Cather, eds. Janis P. Stout and Andrew Jewell (Knopf, 2013), 364.